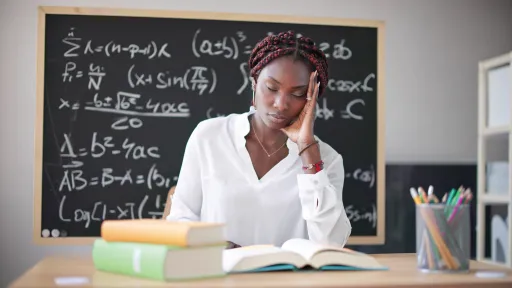

Teachers are the most burned-out professionals in the United States. In a 2024 Rand report, based on results from the 2024 State of the American Teacher survey, 60% of teachers in the U.S. feel burned out at work versus 33% of comparable working adults.

While staff shortages and declining salaries are common culprits, according to the National Association of Independent Schools, heavy workloads are another key issue. In a 2024 Pew Research Center survey, 84% of teachers said that due to overwhelming workloads, they don’t have enough time in the day for lesson planning, collaborating with colleagues, and grading.

The result? Educators are fleeing the profession, leaving fewer teachers to do more work. “The health and well-being of educators, influenced by workload and work intensification, [are] related to rates of attrition,” according to the journal Educational Review.

AI to the Rescue?

The National Education Association calls burnout “a temporary condition in which an educator has exhausted the personal and professional resources necessary to do the job.”

It only makes sense, then, that providing more and better resources can help alleviate teacher burnout. AI is perfectly poised to provide some of those resources.

True, AI won’t increase teacher salaries or magically hire more staff. But it can lift some of the burden of heavy workloads by streamlining repetitive tasks, augmenting teachers’ creativity in the classroom, giving teachers time for more impactful and meaningful work, and freeing up mental bandwidth for teachers to do self-care. In fact, teachers who use the AI-based educational platform Toddle, for example, are already saving eight hours a week, according to Cindy Blackburn, the company’s director of learning and engagement. And educators at Saddle River Day School in Saddle River, New Jersey, have reported up to an 80% decrease in prep time using the school’s custom-built AI platform, said Kevin Merges, Ed.D., Saddle River Day School’s chief global impact officer.

Understanding the Role of AI

The average teacher spends about 50 hours per week on noninstructional, nonstudent-facing tasks, according to a McKinsey & Co. survey. AI tools can take on some of these tasks so educators can do what they’re best at. However, some teachers are wary that AI will also take over the human, creative side of their jobs. Here’s how to find the balance.

Keep AI in its Place

Educators and technology leaders should keep in mind what humans are good at versus what AI is good at. Dan Olexio, assistant head of school for academic affairs at Columbus Academy in Gahanna, Ohio, cites author and educational creativity expert John Spencer, who says AI is ideal for:

- Synthesizing information

- Generating examples

- Role-playing

- Creating systems using predictive analytics

- Analyzing problems

- Helping people understand concepts

On the other hand, some of the tasks that are best suited for human educators (and learners) include:

- Understanding and using context

- Having divergent thinking

- Exercising creativity and curiosity

- Developing empathy

- Creating innovative solutions

“That’s the value added,” Olexio said. “Those things are what we as teachers can be doing to help our students learn.” Using AI for the first list of capabilities gives educators more time to focus on the second list.

Use AI to Kick Off the Process

To keep AI from taking over the best parts of their jobs — while still getting the burnout-busting benefits — teachers can use it to jump-start their creativity. For example, ChatGPT can easily come up with ideas for a lesson plan or a reading list, and the educator can then tinker with the basic information ChatGPT provides to develop the perfect plan.

Understanding the role of AI will not only help teachers use the tools in ways that support and complement their expertise, helping to prevent burnout, but it will also help assuage educators who are worried that AI will take over their jobs.

Getting Educators on Board With AI

Educators may resist AI due to concerns about job security, fears of being perceived as “cheating,” or frustration with the learning curve for AI tools. But with thoughtful planning, technology leaders can play a role in inspiring teachers with how AI can help them enhance productivity and alleviate burnout.

Here are tips and talking points to help technology leaders handle the most common objections educators have about AI.

Objection 1: I don’t understand what AI is and why we need it.

When introducing AI tools, it’s crucial to hold meetings that address common concerns and showcase practical examples of how AI can streamline tasks and help prevent burnout. These meetings might even highlight success stories from other schools using similar AI tools.

For example, the middle and upper school divisions at Columbus Academy brought in outside technology professionals to lead sessions on AI for one of the school’s professional development days.

“We have faculty all over the map in terms of exposure to and use of AI, thoughts about AI, fear of AI, and so on,” said Olexio. “We wanted our faculty to get hands-on experience with potential tools they could use for streamlining their own processes.”

The presenters also discussed how and when to introduce AI tools to students.

“The day went well,” Olexio said. “[The presenters] shared information during several sessions, and at the end of the day, we gave our faculty space to play with the tools on something practical to them.”

Blackburn suggested incorporating written “pre-mortems” into these meetings, as well. Have teachers write down every reason they can think of as to why they shouldn’t use AI in their school. Then, sort the objections into teacher-facing reasons and student-facing reasons, see what themes emerge, and tackle them one at a time.

Objection 2: I’m afraid AI is going to take my job.

AI will empower teachers, not replace them. “We don’t want teacher-bots standing in the front of the room,” said Merges. “We actually see AI as increasing our need for teachers. We’re going to use AI not to drive up the section size, but to drive it down ... so we can have smaller classes where students get more contact time with teachers.”

Objection 3: AI won’t work for my particular needs.

Educators who voice this objection may not be familiar with the variety of AI tools available — or even that AI is now built into many tools they might already be using. Again, holding sessions to introduce these tools is key.

Going even further, some independent schools that have the interest and the means are exploring the development of custom-built AI platforms that integrate the most useful tools for their teachers.

For example, Saddle River Day School worked with a company in India to develop a centralized AI platform. Feedback from educators played a big role in the final product. “Our teachers had a lot of meetings to determine which tools they wanted and which they didn’t need,” said Merges.

Students at the school are now able to get instant answers to their questions and access lessons, assignments, practice tests, and grades (which are also calculated by the AI), Merges said. The information students see can even be personalized to their interests, learning styles, and strengths.

“One of the first things we noticed was that the panicky emails the night before a quiz slowed down,” Merges said. Seeing that answering emails is one of the tasks that overwhelm teachers, this small win could make a big impact on teacher burnout.

“If there’s a workflow that saves you time, while getting results that are as good as or better than before in a manner that’s less stressful for you, why wouldn’t you play with that?”

Dan Olexio, Columbus Academy

Objection 4: I don’t know which tasks I can use AI for.

Teachers may already know they can use AI to offload repetitive and monotonous tasks. But which tasks? Blackburn recommended teachers conduct a time audit to understand how they’re using their time and identify areas where AI can automate or streamline their work. “A time audit is an eye-opener for many teachers,” she said.

To conduct a time audit, educators spend three days breaking down their time into 15-minute chunks, recording what they do during each time chunk, and analyzing the results for themes and patterns. For example, they may find that a certain set of tasks brings them joy, while another set feels like a waste of time that takes them away from their students. (See sidebar at left for ideas of tasks teachers can hand over to AI tools.)

Objection 5: Using AI is cheating.

Whether to let students use AI is a hotly debated topic. But what about when educators use AI to take work off their plate? Is this cheating? Are teachers cutting corners in service of avoiding burnout?

“Let’s get past this idea that using AI as a teacher is cheating,” said Olexio. “If there’s a workflow that saves you time, while getting results that are as good as or better than before in a manner that’s less stressful for you, why wouldn’t you play with that?”

One big reason that holds educators back is that when a parent sends a child to an independent school, they expect that teachers will put personalized effort into that student.

If a teacher is using AI to, say, write student reports, it may feel like the teacher is not putting personalized effort into describing the student. But “I would argue I spent about the same amount of time,” said Olexio. “In some ways, my end result was better because it was less about trying to construct sentences and more about thinking about the student and coming up with the descriptors I put into ChatGPT.”

Not to mention, when educators use AI to take repetitive tasks off their hands, they have more time to spend one-on-one with each student.

Objection 6: I don’t want to just trade one task for another.

AI follows that old engineering maxim, GIGO: garbage in, garbage out. But what’s the point of using AI to decrease educator workloads if the teachers have to use that time to learn prompt engineering and other AI-related tasks instead?

“Generative AI is here to stay, and every tool has an adoption curve and requires the building of literacy skills,” said Blackburn.

Luckily, the internet is full of free lessons in prompt engineering that can help educators learn to word prompts in ways that quickly and efficiently get them the results they need, personalize the tool’s responses to their particular situation, and reduce the threat of incorrect or misleading results produced by AI.

While AI tools require a time commitment on the front end, teachers save even more time on the back end, said Blackburn. “Some of the things you’re capable of creating — and the speed with which you’re capable of creating them — it’s phenomenal,” she said.

Double Down on Teacher Support

“For thousands of years, we’ve had schools ... and the only thing all forms of schools have had in common is teachers,” said Merges. “We need to remember that. Double down on supporting teachers so they don’t get burnout, and reinforce the time they have to meet with the students and help them grow as people.”

By understanding the causes of burnout, listening to teacher feedback, choosing (or creating) the right AI tools, and supporting teachers in their use, independent schools can accomplish all of this — and more.