Creativity is the competence to leverage self-interests, motivation, imagination, and prior knowledge in flexible ways[1] to generate, evaluate, or improve ideas; imagine new ways of solving problems;[2] forge new connections — across content and people;[3] create new understanding; or communicate thinking through writing, drawing, voice, music, or any other means of expression.[4]

Creativity has long been heralded as a critical skill for today’s students. The Partnership for 21st Century Skills (P21) included it as one of their 4Cs before the turn of the century. In 2015, the World Economic Forum listed it as one of the top three skills — just behind complex problem solving and critical thinking — for success in 2020. The 2017 National Education Technology Plan (NETP) identified it as an essential component for learning, advocating that ALL students need to become active creators with technology to narrow an emerging Digital Use Divide.

A 2019 Gallup study on the state of creativity in schools found that when students experience more creative classrooms and use technology in meaningful ways to demonstrate their creativity, they are more likely to engage in problem-solving, demonstrate critical thinking, make connections across subject areas, and have deeper understanding as well as greater retention of content. However, not all students experience these opportunities. A 2022 report from Project Tomorrow, “ Beyond the Homework Gap: Leveraging Technology to Support Equity of Learning Experiences in School,” found that in schools serving Black and Latino/a students as well as those experiencing poverty, teachers were 54% more likely to report concerns about the equity of students’ creative learning experiences, and the students in those schools described fewer creative learning opportunities than their peers.

At The Learning Accelerator (TLA), we identified a core challenge in the field: although teachers often express the desire to learn how to foster creativity, they don’t always know how to factor it into their instructional design or know whether their students are developing the creativity skills that will benefit them in the future. To address these challenges, we have produced a number of openly available resources for technology leaders and educators. First, we developed and piloted two survey instruments to understand teacher as well as student perceptions and behaviors related to creativity. Then, in collaboration with a small cadre of educators from both independent and public schools, we built a framework to help educators iteratively design new learning experiences that nurture student creativity while providing students, leaders, and coaches with reflection and feedback protocols.

Teacher and Student Creativity Survey Design

To inform the design of the two surveys, we conducted a literature review focused on creativity with technology. Based on that analysis, we broke the overarching theory of creativity into eight separate constructs — broad concepts or factors — based on the ideas of creative thinking, innovation, and creativity specific to technology. For the teacher survey, we then piloted questions asking about attitudes towards creativity in learning (perception) as well as teaching for creativity (behaviors). Our analysis found that while this survey could be reliable, it was not a valid measure of those constructs.

Based on that analysis, we revised the survey and reorganized it into four dimensions based on the 4Ps of Creativity: Person, Press (which we later defined as Place), Process — which was divided into creative communication, creative problem-solving, and creative thinking — and Product. Then, we used this new 4Ps structure to design and test an accompanying student survey. The results of both pilots are described below.

Teacher Creativity Survey

Our analysis revealed that while teachers value creativity (e.g., perception), they do not always demonstrate practices that would foster it in the classroom (e.g., reported behavior). At the same time, although a majority of the respondents felt supported by their leaders, they also indicated that they have not received adequate professional learning to design classroom experiences that foster creativity. Particularly given this finding, school leaders may choose to use this survey to identify areas or topics for future professional development as well as potential bright spot classrooms that could help other educators or coaches understand what could be possible.

Student Creativity Survey

Seven middle and high school teachers from four schools (two charter, one public, and one independent) asked their students to complete the student creativity survey, allowing us to collect 324 responses. Collectively, these schools served a diverse student population from across the country. Our analysis of the data led to some interesting observations, though given the limited number of participating classes, we cannot consider them representative findings.

In general, the students indicated that they want to create things that help others and work on class projects that are important to them. They also agreed or strongly agreed that they possess the skills to come up with novel solutions by relying on their prior knowledge. In contrast, when asked how often their teachers ask them to share their ideas, a majority indicated that it only occurs sometimes. Similar to the teacher survey findings, student perceptions rated higher than their behaviors. Of note, the least frequently reported behaviors were those associated with whether students used their imagination, made connections to the real world, or were rewarded for showing ideas in digital form.

Putting the Surveys Into Action

Based on the teachers’ feedback on the students’ experiences taking the survey, we reduced the number of questions in this revised survey. Requiring less time to complete, teachers could use it throughout the year to inform the design of different activities or projects. Leaders could then look at changes over time to identify opportunities for professional learning or as evidence of continuous improvement. However, this data alone does not help teachers understand HOW to design creative learning opportunities for their students, leading us to develop a framework and protocol to support instructional design, reflection, and feedback.

Creativity in the Technology-Rich Classroom: Framework & Protocol

Educators can find abundant discussion about the need for students to develop creativity skills – but few resources exist to actually help them design and assess experiences that would create learning opportunities that support creativity. At TLA, we produced an openly-available framework to help educators, instructional coaches, leaders, and peer observers design and assess creative learning experiences using technology with an overarching goal of making ongoing, iterative instructional improvements. In addition, this resource contains a student version to help children reflect on these opportunities and articulate what (and whether) they learned.

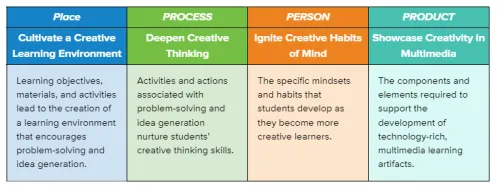

We again chose the 4Ps[5] – Place (which Rhodes refers to as Press), Process, Person, and Product – as the overarching framework. Typically, discussion of creativity and technology revolves around Product – the multimedia created as part of a lesson or activity. However, the 4Ps takes a broader approach, acknowledging additional factors such as the required learning conditions (Place), methods to encourage students' thinking (Process), and students’ habits of mind (Person).

How To Use the 4Ps Framework

The 4Ps framework will help inform the design of different learning opportunities and measure ongoing, iterative improvements. Each section of the 4Ps framework contains specific elements, and to understand what they may look like in practice, concrete indicators that describe different levels of implementation: emerging, progressing, and transforming.

This framework is most powerful when used as a brainstorming, idea-generating, design, and reflection tool. Educators are encouraged to focus on one of the 4Ps at a time and then choose one or two elements that feel most relevant to their plans and are not expected to take on the entire framework at once. For technology leaders, each section of the framework includes a feedback tool to support future improvements.

Putting the Framework Into Action

The most important concept related to the framework is iterative, incremental improvement. The goal of this framework is two-fold: to help educators create new learning opportunities and for students to have the language that will allow them to reflect on those experiences. In addition, when provided to instructional technology specialists, principals, or technology coaches, the framework can be used as a feedback, observation, and coaching tool to help teachers with the design of their lessons or activities. Finally, we hope that the 4Ps provide schools with shared language to concretely describe what creativity looks like in their classrooms and how to create experiences that will allow it to take hold.

References

Hatano, G., & Inagaki, K. (1986). Two courses of expertise. In H. Stevenson, H. Azuma, & K. Hakuta (Eds.), Child development and education in Japan (pp. 262–272). New York, NY: Freeman.

Gallup. (2019). Creativity in Learning. https://www.gallup.com/education/267449/creativity-learning-transformative-technology-gallup-report-2019.aspx

OECD. (2021). PISA 2021 Creative Thinking Framework. https://www.oecd.org/pisa/publications/PISA-2021-creative-thinking-framework.pdf

Gregory, E., Hardiman, M., Yarmolinskaya, J., Rinne, L. & Limb, C. (2013). Building creative thinking in the classroom: From research to practice.International Journal of Educational Research, 62, 43–50.

Rhodes, M. (1961). An Analysis of Creativity. The Phi Delta Kappan, 42(7), 305–310. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20342603